The subjective nature of loneliness, and stigmatisation of those who feel lonely, can make it difficult to identify loneliness in others; be it in social, professional or clinical situations.

Knowing the risk factors for loneliness can help to identify those who might be at risk, and asking the right questions is necessary to recognise those who may be in need of help.

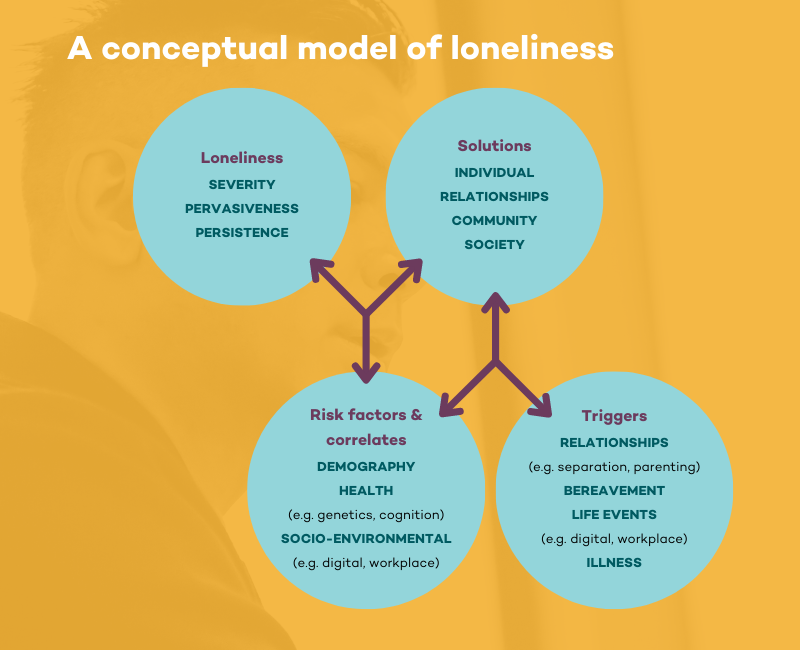

A conceptual model of loneliness (Figure 1, below) developed by Dr Michelle Lim and colleagues at Melbourne’s Swinburne University helps to explain how life’s circumstances might precipitate loneliness in individuals.

It identifies four components, the specifics of which will be unique for everyone.

Risk factors

The Campaign to End Loneliness reports risk factors and triggers for loneliness in different demographic groups, which include:

Detailed information about triggers and risk factors for loneliness in different population groups in Australia is not available.

Asking the right questions

Practical guidance for using these measures, to ensure that responses are valid, is available.

Even though it has been suggested that such measures “can diagnose if a patient has abnormally high levels of loneliness”, their validation for different patient populations is not well established, but work is underway.

For example, a recent study says loneliness can be used to predict one-year mortality in patients with coronary heart disease.

Lonely men are more stigmatised than lonely women, which might be why men are more reluctant to admit to feeling lonely.

Hence, indirect measures of loneliness are more likely than direct measures to accurately identify lonely men. The same might be true of different cultural groups, or people of different ages.

Mitigating the adverse effects of loneliness on health requires accurate ways to identify the problem in everyone, but the conceptual model of loneliness suggests we need not wait for ideal evidence to guide practice.

Simply asking patients about their social wellbeing creates a connection with them that may improve feelings of isolation and help address this wicked problem.