The “male loneliness epidemic” is a term used to describe significant and growing rates of isolation and lack of connection among men. It’s a lightning rod topic but is there data to back up its validity? And what’s really to blame?

The social isolation measures that helped to save thousands of lives during the COVID-19 pandemic made us realise how important the company of friends and family is. The number of Australians who report feeling lonely went from one in four pre-COVID to one in two amid lockdowns.

The experience also reminded us about the negative effect that loneliness can have on our health and wellbeing. Strong and supportive relationships are linked to lower rates of anxiety and depression, higher self-esteem, greater empathy, a stronger immune system, and a longer life. Lack of social connection can have a greater impact on health than obesity and smoking.

Loneliness isn’t just about having people around you. You can be alone and not feel lonely at all, or you can be surrounded by people and still feel lonely.

Firstly, how do we measure loneliness?

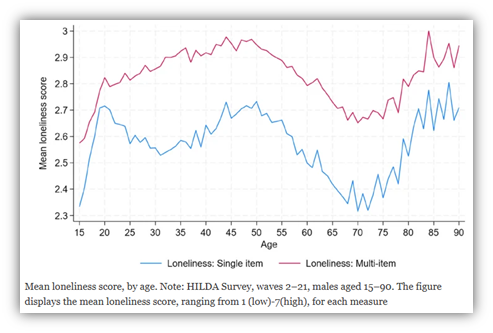

When researchers want to measure loneliness in a group of people, they simply ask them. Asking how much someone agrees with the statement, “I often feel very lonely” on a scale from one to seven provides a valid measure of whether someone is lonely. Another common measurement comes from responses to three questions about how often someone feels left out, isolated or lacks companionship. These measures are about the feeling of loneliness, regardless of how much social contact someone has.

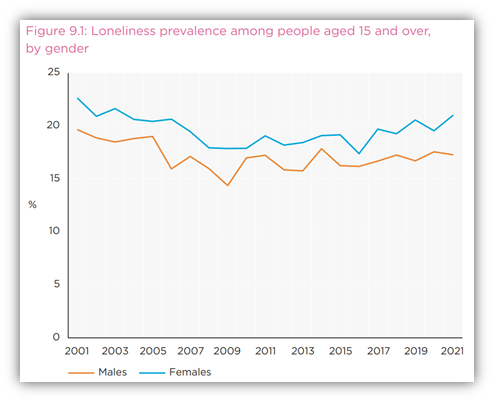

Loneliness in Australia has been measured for the last 25 years by the yearly HILDA (Household, Income Labour and Dynamics) survey. These studies show that between 14-20% of Australian males (and 17-23% of females) aged over 15 years were lonely between 2001-2021, averaging at about 17% overall.

The prevalence of loneliness in males and females didn’t change a lot between 2001 and 2021 but our population grew by four million people over that time. In 2001, there were about 15.6 million people aged over 15 years; in 2021 there were 20.7 million. When you do the maths, that’s about one million more lonely people over the 20-year period.

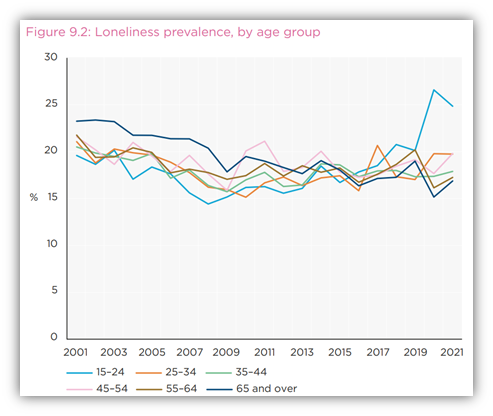

When you break down the data by age group you can see that the prevalence of loneliness has changed in different ways for people of different ages. Loneliness has gradually decreased in older Australians but increased in younger people in recent years; especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Age-related differences in the prevalence of loneliness are well established. Healthy Male’s ‘What’s in the Way?’ survey of 1200 Australian men (which was done just as COVID vaccines were being rolled out) showed that loneliness is more prevalent in younger than older men, consistent with HILDA data.

A recent analysis of HILDA data shows in greater detail how age, life events and other factors interact to affect loneliness in Australian males.

So, are men experiencing a loneliness epidemic?

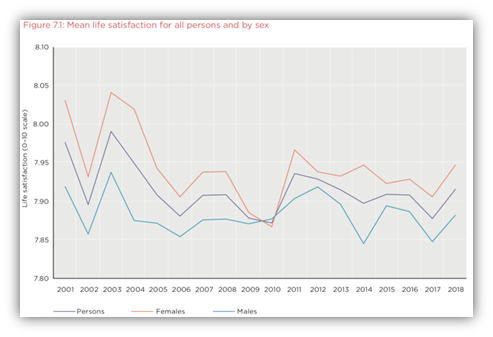

On face value, the HILDA data make it look like females are lonelier than males. HILDA data also suggest that life satisfaction is (slightly) higher in females than males.

The higher prevalence of loneliness in females might be because men are less likely to admit feeling lonely. The HILDA survey measures loneliness using the single “I often feel very lonely” statement. For males, when you use the three-question measurement you find higher rates of loneliness than for the single question. This might also explain why recent measures of loneliness using the single question detect higher rates of loneliness in young males: maybe they’re now more willing to say they feel lonely.

It’s not surprising that you get different results when you use different measurement techniques, or when you use the same measurement in different groups of people. This makes comparisons between different measures and different groups of people difficult.

We can’t know for sure if these apparent differences are ‘real’ or just an artefact of a measurement technique that has a gender bias.

All of these survey findings reflect the range of life experiences of Australian men, and their variable effects on loneliness. Perhaps it’s a sign of the times that we’re so aware of loneliness and the stress it causes, given other stresses like the increasing cost of living, effects of social media and the like

Another thing that has increased awareness of loneliness is our increasing understanding of the links between loneliness, social isolation and poor health, prompting the US Surgeon General to declare an “epidemic of loneliness”.

While the data say that the prevalence of loneliness hasn’t changed drastically over the last 25 years, we are certainly more willing to talk about it and more aware of its effects; and that’s a good thing.